If you know your mother tongue and then you widen out to learn all the languages of the world, that's empowerment. If you know all the languages of the world and not your mother tongue, that is not empowerment: that is enslavement.--Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

I've heard the phrase "decolonizing the mind" tossed about a lot, but didn't know until last night that the book Decolonising the Mind was written by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, a seminal Kenyan writer who's very active in supporting mother tongues and encouraging translation and understanding across less-dominant languages. He's giving a lecture at the nearby university today, but yesterday there was a much more intimate event: a screening of a film about him by the Kenyan director Ndirangu Wachanga, followed by a conversation with the two of them.

Ndirangu Wachanga (photo source)

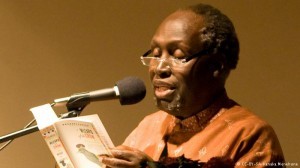

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o (photo source)

( Read more... )

Is English an African language?

In interviewing African intellectuals, Wachanga likes to ask that question. No? Yes? Partially? The responses and reasoning people gave were absorbing. Ngũgĩ had lots to say about it--and so did one of the audience members, during the question-and-answer session. She came to America as a young child, with her mother. She said, "When I'm with my Chinese friends, we all talk in English--but when they go home, they talk in Chinese. When I'm with my Brazilian friends, we all talk in English--but when they go home, they talk in Portuguese. But when I go home, I talk in English." There wasn't a chance for her to finish her thought and say how she felt about that, or what her own feelings were on the question of English as an African language, but even just as much as she said was thought provoking.

All in all, it was such an energizing experience. I came away with so many things I want to read and think about, and so many people--featured in Wachanga's film--whom I want to find out more about. Three commentators in particular: Wangui Wa Goro (a translator), Grant Farred (quoted above; he's a professor of English and African studies), and Dagmawi Woubshet, an Ethiopian (but teaching in the United States) scholar of African and African American literature. Those three were especially passionate.