If you know your mother tongue and then you widen out to learn all the languages of the world, that's empowerment. If you know all the languages of the world and not your mother tongue, that is not empowerment: that is enslavement.--Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

I've heard the phrase "decolonizing the mind" tossed about a lot, but didn't know until last night that the book Decolonising the Mind was written by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, a seminal Kenyan writer who's very active in supporting mother tongues and encouraging translation and understanding across less-dominant languages. He's giving a lecture at the nearby university today, but yesterday there was a much more intimate event: a screening of a film about him by the Kenyan director Ndirangu Wachanga, followed by a conversation with the two of them.

Ndirangu Wachanga (photo source)

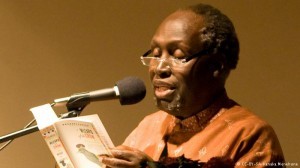

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o (photo source)

Wachanga started off the afternoon, talking about his project, which is to make recordings, audiovisual records, of important figures in East African history, which will be stored in an open-access repository. He talked about what happened in Zimbabwe, on the eve of independence, how there was mass destruction of records--extra shredders brought in, and when those were insufficient, wholesale burning:

Our past was cremated ... In the absence of archival materials, I turned to testimonies ... I took my camera and started recording my conversations with scholars, artists, [etc.]

One of those people is Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. He was born in a village in Kenya in 1938, and already in high school he was contributing stories to the school literary magazine. He went on to the University of Makerere in Uganda, then off to Leeds University, experienced Kenya's independence, published bunches of novels--and then started writing plays, and in Kikuyu, not English--which got him in trouble with the government. As Abena Busia (a Ghanaian writer who teaches at Rutgers) says in the film, "When he started writing dramas in the language of the people, he got arrested." He spoke about the experience: "They came at night and said they just wanted to ask me a few questions . . . a few questions turned into a year's detention." He went into exile, came back, has had multiple attempts on his life, and now is teaching at the University of Irvine.

Along the way he made the decision to write all future novels in Kikuyu or Swahili, but not English. "Some people think that I hate English, but I love English," he said. But English has plenty of champions and plenty of people writing in it. He opposes a tendency toward monolingualism: "Nature herself is not monolingual," he said.

Every language is like a house full of treasure [and learning language is a key.] The more keys I have, the more treasure houses I can open.

English doesn't have to be the hub language, mediating all exchanges. People can write in their own language, and translation can happen directly from those languages into each other. He has a short story (originally written for one of his daughters as a Christmas present), "The Upright Revolution" (a story of the struggle between arms and legs for which should be dominant), which has been translated into 30 African languages. He said he's received inquiries about having it translated into Portuguese and other languages. One attendee at this event greeted him in Ojibwe, her ancestral language, and said that it was thanks to reading his works that she'd embarked on learning her language. He invited her to translate the story into Ojibwe.

One commentator, Grant Farred, said something interesting about translation:

Translation is a struggle secondarily with language; its a struggle first with thinking.

Yes: speaking, reading, translating, and sharing in multiple languages is absolutely mind altering and mind expanding.

Is English an African language?

In interviewing African intellectuals, Wachanga likes to ask that question. No? Yes? Partially? The responses and reasoning people gave were absorbing. Ngũgĩ had lots to say about it--and so did one of the audience members, during the question-and-answer session. She came to America as a young child, with her mother. She said, "When I'm with my Chinese friends, we all talk in English--but when they go home, they talk in Chinese. When I'm with my Brazilian friends, we all talk in English--but when they go home, they talk in Portuguese. But when I go home, I talk in English." There wasn't a chance for her to finish her thought and say how she felt about that, or what her own feelings were on the question of English as an African language, but even just as much as she said was thought provoking.

All in all, it was such an energizing experience. I came away with so many things I want to read and think about, and so many people--featured in Wachanga's film--whom I want to find out more about. Three commentators in particular: Wangui Wa Goro (a translator), Grant Farred (quoted above; he's a professor of English and African studies), and Dagmawi Woubshet, an Ethiopian (but teaching in the United States) scholar of African and African American literature. Those three were especially passionate.

no subject

Date: 2016-04-07 03:13 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-07 03:34 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-07 05:01 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-07 08:33 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-07 07:30 pm (UTC)Absolutely.

no subject

Date: 2016-04-07 08:33 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-07 08:37 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-07 08:41 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-07 08:49 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-07 08:51 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-08 01:35 am (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-08 12:17 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-08 02:06 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-08 11:01 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-08 12:31 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2016-04-08 12:37 pm (UTC)And it wasn't just him, it was the filmmaker too, and the other people in the audience, like the young woman who spoke last about speaking English at home, or Sonya Atalay, the woman (she's a UMass prof) who'd reclaimed her ancestral language, or the other folks interviewed in the film. I'm so 100 percent behind Wachanga's project--this event really showed how powerful it is.